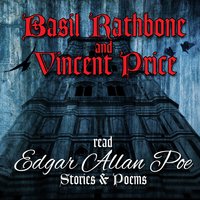

Berenice - Vincent Price, Basil Rathbone

- Año de lanzamiento: 2013

- Duración: 23:52

A continuación la letra de la canción Berenice Artista: Vincent Price, Basil Rathbone Con traducción

Letra " Berenice "

Texto original con traducción

Berenice

Vincent Price, Basil Rathbone

Оригинальный текст

MISERY is manifold.

The wretchedness of earth is multiform.

Overreaching the

wide

horizon as the rainbow, its hues are as various as the hues of that arch,

—as distinct too,

yet as intimately blended.

Overreaching the wide horizon as the rainbow!

How is it

that from beauty I have derived a type of unloveliness?

—from the covenant of

peace a

simile of sorrow?

But as, in ethics, evil is a consequence of good, so, in fact,

out of joy is

sorrow born.

Either the memory of past bliss is the anguish of to-day,

or the agonies

which are have their origin in the ecstasies which might have been.

My baptismal name is Egaeus;

that of my family I will not mention.

Yet there are no

towers in the land more time-honored than my gloomy, gray, hereditary halls.

Our line

has been called a race of visionaries;

and in many striking particulars —in the

character

of the family mansion —in the frescos of the chief saloon —in the tapestries of

the

dormitories —in the chiselling of some buttresses in the armory —but more

especially

in the gallery of antique paintings —in the fashion of the library chamber —and,

lastly,

in the very peculiar nature of the library’s contents, there is more than

sufficient

evidence to warrant the belief.

The recollections of my earliest years are connected with that chamber,

and with its

volumes —of which latter I will say no more.

Here died my mother.

Herein was I born.

But it is mere idleness to say that I had not lived before

—that the

soul has no previous existence.

You deny it?

—let us not argue the matter.

Convinced myself, I seek not to convince.

There is, however, a remembrance of

aerial

forms —of spiritual and meaning eyes —of sounds, musical yet sad —a remembrance

which will not be excluded;

a memory like a shadow, vague, variable, indefinite,

unsteady;

and like a shadow, too, in the impossibility of my getting rid of it

while the

sunlight of my reason shall exist.

In that chamber was I born.

Thus awaking from the long night of what seemed,

but was

not, nonentity, at once into the very regions of fairy-land —into a palace of

imagination

—into the wild dominions of monastic thought and erudition —it is not singular

that I

gazed around me with a startled and ardent eye —that I loitered away my boyhood

in

books, and dissipated my youth in reverie;

but it is singular that as years

rolled away,

and the noon of manhood found me still in the mansion of my fathers —it is

wonderful

what stagnation there fell upon the springs of my life —wonderful how total an

inversion took place in the character of my commonest thought.

The realities of

the

world affected me as visions, and as visions only, while the wild ideas of the

land of

dreams became, in turn, —not the material of my every-day existence-but in very

deed

that existence utterly and solely in itself.

-

Berenice and I were cousins, and we grew up together in my paternal halls.

Yet differently we grew —I ill of health, and buried in gloom —she agile,

graceful, and

overflowing with energy;

hers the ramble on the hill-side —mine the studies of

the

cloister —I living within my own heart, and addicted body and soul to the most

intense

and painful meditation —she roaming carelessly through life with no thought of

the

shadows in her path, or the silent flight of the ravenwinged hours.

Berenice!

—I call

upon her name —Berenice!

—and from the gray ruins of memory a thousand

tumultuous recollections are startled at the sound!

Ah!

vividly is her image

before me

now, as in the early days of her lightheartedness and joy!

Oh!

gorgeous yet

fantastic

beauty!

Oh!

sylph amid the shrubberies of Arnheim!

—Oh!

Naiad among its

fountains!

—and then —then all is mystery and terror, and a tale which should not be told.

Disease —a fatal disease —fell like the simoom upon her frame, and, even while I

gazed upon her, the spirit of change swept, over her, pervading her mind,

her habits,

and her character, and, in a manner the most subtle and terrible,

disturbing even the

identity of her person!

Alas!

the destroyer came and went, and the victim

—where was

she, I knew her not —or knew her no longer as Berenice.

Among the numerous train of maladies superinduced by that fatal and primary one

which effected a revolution of so horrible a kind in the moral and physical

being of my

cousin, may be mentioned as the most distressing and obstinate in its nature,

a species

of epilepsy not unfrequently terminating in trance itself —trance very nearly

resembling positive dissolution, and from which her manner of recovery was in

most

instances, startlingly abrupt.

In the mean time my own disease —for I have been

told

that I should call it by no other appelation —my own disease, then,

grew rapidly upon

me, and assumed finally a monomaniac character of a novel and extraordinary

form —

hourly and momently gaining vigor —and at length obtaining over me the most

incomprehensible ascendancy.

This monomania, if I must so term it, consisted in a morbid irritability of

those

properties of the mind in metaphysical science termed the attentive.

It is more than

probable that I am not understood;

but I fear, indeed, that it is in no manner

possible to

convey to the mind of the merely general reader, an adequate idea of that

nervous

intensity of interest with which, in my case, the powers of meditation (not to

speak

technically) busied and buried themselves, in the contemplation of even the most

ordinary objects of the universe.

To muse for long unwearied hours with my attention riveted to some frivolous

device

on the margin, or in the topography of a book;

to become absorbed for the

better part of

a summer’s day, in a quaint shadow falling aslant upon the tapestry,

or upon the door;

to lose myself for an entire night in watching the steady flame of a lamp,

or the embers

of a fire;

to dream away whole days over the perfume of a flower;

to repeat

monotonously some common word, until the sound, by dint of frequent repetition,

ceased to convey any idea whatever to the mind;

to lose all sense of motion or

physical

existence, by means of absolute bodily quiescence long and obstinately

persevered in;

—such were a few of the most common and least pernicious vagaries induced by a

condition of the mental faculties, not, indeed, altogether unparalleled,

but certainly

bidding defiance to anything like analysis or explanation.

Yet let me not be misapprehended.

—The undue, earnest, and morbid attention thus

excited by objects in their own nature frivolous, must not be confounded in

character

with that ruminating propensity common to all mankind, and more especially

indulged

in by persons of ardent imagination.

It was not even, as might be at first

supposed, an

extreme condition or exaggeration of such propensity, but primarily and

essentially

distinct and different.

In the one instance, the dreamer, or enthusiast,

being interested

by an object usually not frivolous, imperceptibly loses sight of this object in

wilderness of deductions and suggestions issuing therefrom, until,

at the conclusion of

a day dream often replete with luxury, he finds the incitamentum or first cause

of his

musings entirely vanished and forgotten.

In my case the primary object was

invariably

frivolous, although assuming, through the medium of my distempered vision, a

refracted and unreal importance.

Few deductions, if any, were made;

and those few

pertinaciously returning in upon the original object as a centre.

The meditations were

never pleasurable;

and, at the termination of the reverie, the first cause,

so far from

being out of sight, had attained that supernaturally exaggerated interest which

was the

prevailing feature of the disease.

In a word, the powers of mind more

particularly

exercised were, with me, as I have said before, the attentive, and are,

with the daydreamer,

the speculative.

My books, at this epoch, if they did not actually serve to irritate the

disorder, partook, it

will be perceived, largely, in their imaginative and inconsequential nature,

of the

characteristic qualities of the disorder itself.

I well remember, among others,

the treatise

of the noble Italian Coelius Secundus Curio «de Amplitudine Beati Regni dei»;

St.

Austin’s great work, the «City of God»;

and Tertullian «de Carne Christi,»

in which the

paradoxical sentence «Mortuus est Dei filius;

credible est quia ineptum est:

et sepultus

resurrexit;

certum est quia impossibile est» occupied my undivided time,

for many

weeks of laborious and fruitless investigation.

Thus it will appear that, shaken from its balance only by trivial things,

my reason bore

resemblance to that ocean-crag spoken of by Ptolemy Hephestion, which steadily

resisting the attacks of human violence, and the fiercer fury of the waters and

the

winds, trembled only to the touch of the flower called Asphodel.

And although, to a careless thinker, it might appear a matter beyond doubt,

that the

alteration produced by her unhappy malady, in the moral condition of Berenice,

would

afford me many objects for the exercise of that intense and abnormal meditation

whose

nature I have been at some trouble in explaining, yet such was not in any

degree the

case.

In the lucid intervals of my infirmity, her calamity, indeed,

gave me pain, and,

taking deeply to heart that total wreck of her fair and gentle life,

I did not fall to ponder

frequently and bitterly upon the wonderworking means by which so strange a

revolution had been so suddenly brought to pass.

But these reflections partook

not of

the idiosyncrasy of my disease, and were such as would have occurred,

under similar

circumstances, to the ordinary mass of mankind.

True to its own character,

my disorder

revelled in the less important but more startling changes wrought in the

physical frame

of Berenice —in the singular and most appalling distortion of her personal

identity.

During the brightest days of her unparalleled beauty, most surely I had never

loved

her.

In the strange anomaly of my existence, feelings with me, had never been

of the

heart, and my passions always were of the mind.

Through the gray of the early

morning —among the trellissed shadows of the forest at noonday —and in the

silence

of my library at night, she had flitted by my eyes, and I had seen her —not as

the living

and breathing Berenice, but as the Berenice of a dream —not as a being of the

earth,

earthy, but as the abstraction of such a being-not as a thing to admire,

but to analyze —

not as an object of love, but as the theme of the most abstruse although

desultory

speculation.

And now —now I shuddered in her presence, and grew pale at her

approach;

yet bitterly lamenting her fallen and desolate condition,

I called to mind that

she had loved me long, and, in an evil moment, I spoke to her of marriage.

And at length the period of our nuptials was approaching, when, upon an

afternoon in

the winter of the year, —one of those unseasonably warm, calm, and misty days

which

are the nurse of the beautiful Halcyon1, —I sat, (and sat, as I thought, alone,

) in the

inner apartment of the library.

But uplifting my eyes I saw that Berenice stood

before

me.

-

Was it my own excited imagination —or the misty influence of the atmosphere —or

the

uncertain twilight of the chamber —or the gray draperies which fell around her

figure

—that caused in it so vacillating and indistinct an outline?

I could not tell.

She spoke no

word, I —not for worlds could I have uttered a syllable.

An icy chill ran

through my

frame;

a sense of insufferable anxiety oppressed me;

a consuming curiosity

pervaded

my soul;

and sinking back upon the chair, I remained for some time breathless

and

motionless, with my eyes riveted upon her person.

Alas!

its emaciation was

excessive,

and not one vestige of the former being, lurked in any single line of the

contour.

My

burning glances at length fell upon the face.

The forehead was high, and very pale, and singularly placid;

and the once jetty

hair fell

partially over it, and overshadowed the hollow temples with innumerable

ringlets now

of a vivid yellow, and Jarring discordantly, in their fantastic character,

with the

reigning melancholy of the countenance.

The eyes were lifeless, and lustreless,

and

seemingly pupil-less, and I shrank involuntarily from their glassy stare to the

contemplation of the thin and shrunken lips.

They parted;

and in a smile of

peculiar

meaning, the teeth of the changed Berenice disclosed themselves slowly to my

view.

Would to God that I had never beheld them, or that, having done so, I had died!

1 For as Jove, during the winter season, gives twice seven days of warmth,

men have

called this clement and temperate time the nurse of the beautiful Halcyon

—Simonides.

The shutting of a door disturbed me, and, looking up, I found that my cousin had

departed from the chamber.

But from the disordered chamber of my brain, had not,

alas!

departed, and would not be driven away, the white and ghastly spectrum of

the

teeth.

Not a speck on their surface —not a shade on their enamel —not an

indenture in

their edges —but what that period of her smile had sufficed to brand in upon my

memory.

I saw them now even more unequivocally than I beheld them then.

The teeth!

—the teeth!

—they were here, and there, and everywhere, and visibly and palpably

before me;

long, narrow, and excessively white, with the pale lips writhing

about them,

as in the very moment of their first terrible development.

Then came the full

fury of my

monomania, and I struggled in vain against its strange and irresistible

influence.

In the

multiplied objects of the external world I had no thoughts but for the teeth.

For these I

longed with a phrenzied desire.

All other matters and all different interests

became

absorbed in their single contemplation.

They —they alone were present to the

mental

eye, and they, in their sole individuality, became the essence of my mental

life.

I held

them in every light.

I turned them in every attitude.

I surveyed their

characteristics.

I

dwelt upon their peculiarities.

I pondered upon their conformation.

I mused upon the

alteration in their nature.

I shuddered as I assigned to them in imagination a

sensitive

and sentient power, and even when unassisted by the lips, a capability of moral

expression.

Of Mad’selle Salle it has been well said, «que tous ses pas etaient

des

sentiments,» and of Berenice I more seriously believed que toutes ses dents

etaient des

idees.

Des idees!

—ah here was the idiotic thought that destroyed me!

Des idees!

—ah

therefore it was that I coveted them so madly!

I felt that their possession

could alone

ever restore me to peace, in giving me back to reason.

And the evening closed in upon me thus-and then the darkness came, and tarried,

and

went —and the day again dawned —and the mists of a second night were now

gathering around —and still I sat motionless in that solitary room;

and still I sat buried

in meditation, and still the phantasma of the teeth maintained its terrible

ascendancy

as, with the most vivid hideous distinctness, it floated about amid the

changing lights

and shadows of the chamber.

At length there broke in upon my dreams a cry as of

horror and dismay;

and thereunto, after a pause, succeeded the sound of troubled

voices, intermingled with many low moanings of sorrow, or of pain.

I arose from my

seat and, throwing open one of the doors of the library, saw standing out in the

antechamber a servant maiden, all in tears, who told me that Berenice was —no

more.

She had been seized with epilepsy in the early morning, and now,

at the closing in of

the night, the grave was ready for its tenant, and all the preparations for the

burial

were completed.

I found myself sitting in the library, and again sitting there

alone.

It

seemed that I had newly awakened from a confused and exciting dream.

I knew that it

was now midnight, and I was well aware that since the setting of the sun

Berenice had

been interred.

But of that dreary period which intervened I had no positive —at

least

no definite comprehension.

Yet its memory was replete with horror —horror more

horrible from being vague, and terror more terrible from ambiguity.

It was a fearful

page in the record my existence, written all over with dim, and hideous, and

unintelligible recollections.

I strived to decypher them, but in vain;

while ever and

anon, like the spirit of a departed sound, the shrill and piercing shriek of a

female voice

seemed to be ringing in my ears.

I had done a deed —what was it?

I asked myself the

question aloud, and the whispering echoes of the chamber answered me, «what was

it?»

On the table beside me burned a lamp, and near it lay a little box.

It was of no

remarkable character, and I had seen it frequently before, for it was the

property of the

family physician;

but how came it there, upon my table, and why did I shudder in

regarding it?

These things were in no manner to be accounted for, and my eyes at

length dropped to the open pages of a book, and to a sentence underscored

therein.

The

words were the singular but simple ones of the poet Ebn Zaiat, «Dicebant mihi sodales

si sepulchrum amicae visitarem, curas meas aliquantulum fore levatas.

«Why then, as I

perused them, did the hairs of my head erect themselves on end, and the blood

of my

body become congealed within my veins?

There came a light tap at the library

door,

and pale as the tenant of a tomb, a menial entered upon tiptoe.

His looks were

wild

with terror, and he spoke to me in a voice tremulous, husky, and very low.

What said

he?

—some broken sentences I heard.

He told of a wild cry disturbing the

silence of the

night —of the gathering together of the household-of a search in the direction

of the

sound;

—and then his tones grew thrillingly distinct as he whispered me of a

violated

grave —of a disfigured body enshrouded, yet still breathing, still palpitating,

still alive!

He pointed to garments;-they were muddy and clotted with gore.

I spoke not,

and he

took me gently by the hand;

—it was indented with the impress of human nails.

He

directed my attention to some object against the wall;

—I looked at it for some

minutes;

—it was a spade.

With a shriek I bounded to the table, and grasped the box that

lay

upon it.

But I could not force it open;

and in my tremor it slipped from my

hands, and

fell heavily, and burst into pieces;

and from it, with a rattling sound,

there rolled out

some instruments of dental surgery, intermingled with thirty-two small,

white and

ivory-looking substances that were scattered to and fro about the floor.

Перевод песни

LA MISERIA es múltiple.

La miseria de la tierra es multiforme.

Sobrepasando el

amplio

horizonte como el arco iris, sus matices son tan variados como los matices de ese arco,

—como distinto también,

sin embargo, tan íntimamente mezclados.

¡Sobrepasando el amplio horizonte como el arco iris!

Cómo es

que de la belleza he derivado una especie de desamor?

—del pacto de

paz un

símil del dolor?

Pero como, en ética, el mal es consecuencia del bien, así, de hecho,

de la alegría es

nace el dolor.

O el recuerdo de la dicha pasada es la angustia de hoy,

o las agonías

que son tienen su origen en los éxtasis que pudieron haber sido.

Mi nombre de bautismo es Egaeus;

la de mi familia no la mencionaré.

Sin embargo, no hay

torres en la tierra más venerada que mis sombríos y grises salones hereditarios.

nuestra linea

ha sido llamada una raza de visionarios;

y en muchos detalles sorprendentes, en el

personaje

de la mansión familiar, en los frescos del salón principal, en los tapices de

la

dormitorios —en el cincelado de algunos contrafuertes de la armería—, pero más

especialmente

en la galería de cuadros antiguos —a la manera de la cámara de la biblioteca— y,

Por último,

en la naturaleza muy peculiar de los contenidos de la biblioteca, hay más de

suficiente

evidencia para justificar la creencia.

Los recuerdos de mis primeros años están relacionados con esa cámara,

y con su

volúmenes, de los cuales no diré más.

Aquí murió mi madre.

Aquí nací yo.

Pero es mera ociosidad decir que no había vivido antes

-que el

el alma no tiene existencia previa.

¿Lo niegas?

—no discutamos el asunto.

Convencido yo mismo, busco no convencer.

Hay, sin embargo, un recuerdo de

aéreo

formas —de ojos espirituales y significativos —de sonidos, musicales pero tristes —un recuerdo

que no serán excluidos;

un recuerdo como una sombra, vago, variable, indefinido,

inestable;

y como una sombra también, en la imposibilidad de deshacerme de ella

mientras que la

existirá la luz del sol de mi razón.

En esa cámara nací yo.

Despertando así de la larga noche de lo que parecía,

pero fue

no, nada, a la vez en las mismas regiones de la tierra de las hadas, en un palacio de

imaginación

—a los dominios salvajes del pensamiento y la erudición monásticos —no es singular

que yo

miré a mi alrededor con un ojo sobresaltado y ardiente, que desperdicié mi infancia

en

libros, y disipé mi juventud en ensoñaciones;

pero es singular que a medida que pasan los años

removida,

y el mediodía de la edad adulta me encontró todavía en la mansión de mis padres, es

maravilloso

qué estancamiento cayó sobre los manantiales de mi vida, ¡maravilloso cuán total

se produjo una inversión en el carácter de mi pensamiento más común.

las realidades de

la

mundo me afectó como visiones, y sólo como visiones, mientras que las ideas salvajes del

tierra de

los sueños se convirtieron, a su vez, no en el material de mi existencia cotidiana, sino en

escritura

esa existencia total y únicamente en sí misma.

-

Berenice y yo éramos primas y crecimos juntas en la casa de mi padre.

Sin embargo, crecimos de manera diferente: yo enfermo de salud y enterrado en la tristeza, ella ágil,

agraciado, y

rebosante de energía;

suyo el paseo por la ladera de la colina; mío, los estudios de

la

claustro —Yo viviendo dentro de mi propio corazón, y adicto en cuerpo y alma a los más

intenso

y dolorosa meditación, vagando descuidadamente por la vida sin pensar en

la

sombras en su camino, o el vuelo silencioso de las horas de alas de cuervo.

Berenice!

-Yo lo llamo

por su nombre: ¡Berenice!

—y de las ruinas grises de la memoria mil

¡Los recuerdos tumultuosos se sobresaltaron con el sonido!

¡Ay!

vívidamente es su imagen

antes de mí

ahora, como en los primeros días de su alegría y alegría!

¡Vaya!

hermosa todavía

fantástico

¡belleza!

¡Vaya!

sílfide entre los arbustos de Arnheim!

-¡Vaya!

Náyade entre sus

fuentes!

—y luego—entonces todo es misterio y terror, y una historia que no debe ser contada.

La enfermedad, una enfermedad fatal, cayó como el simún sobre su cuerpo y, aun cuando yo

la miró, el espíritu del cambio barrió, sobre ella, invadiendo su mente,

sus hábitos,

y su carácter, y, de la manera más sutil y terrible,

molestando incluso a los

identidad de su persona!

¡Pobre de mí!

el destructor iba y venía, y la víctima

-Donde estaba

ella, no la conocí —o ya no la conocí como Berenice.

Entre la numerosa serie de males superinducidos por ese fatal y primario

que efectuó una revolución de un tipo tan horrible en el estado físico y moral

siendo de mi

primo, puede ser mencionado como el más angustioso y obstinado en su naturaleza,

una especie

de la epilepsia que no pocas veces termina en el trance mismo, el trance casi

parecida a una disolucin positiva, y de la cual su manera de recuperarse estaba en

la mayoría

casos, sorprendentemente abruptos.

Mientras tanto, mi propia enfermedad, porque he estado

dicho

que no debería llamarlo por ningún otro apelativo: mi propia enfermedad, entonces,

creció rápidamente sobre

mí, y asumió finalmente un carácter monomaníaco de una novela y extraordinario

forma -

hora y momento ganando vigor, y al final obteniendo sobre mí la mayor parte

ascendencia incomprensible.

Esta monomanía, si debo llamarla así, consistía en una irritabilidad mórbida de

aquellos

propiedades de la mente en la ciencia metafísica denominada atenta.

es mas que

probable que no se me entienda;

pero me temo, en verdad, que no es de ninguna manera

posible que

transmitir a la mente del lector meramente general, una idea adecuada de ese

nervioso

intensidad de inters con la que, en mi caso, los poderes de la meditacin (para no

hablar

técnicamente) ocupados y enterrados, en la contemplación de incluso los más

objetos ordinarios del universo.

Meditar durante largas horas incansables con mi atención clavada en algún frívolo

dispositivo

en el margen, o en la topografía de un libro;

ser absorbido por el

mejor parte de

un día de verano, en una extraña sombra que caía oblicuamente sobre el tapiz,

o sobre la puerta;

perderme durante una noche entera mirando la llama constante de una lámpara,

o las brasas

de un fuego;

soñar días enteros sobre el perfume de una flor;

repetir

monótonamente alguna palabra común, hasta que el sonido, a fuerza de repetición frecuente,

dejó de transmitir cualquier idea a la mente;

perder todo sentido de movimiento o

físico

existencia, por medio de la quietud corporal absoluta larga y obstinadamente

perseverado en;

tales eran algunos de los caprichos más comunes y menos perniciosos inducidos por un

condición de las facultades mentales, no, de hecho, del todo incomparable,

pero ciertamente

desafiando cualquier cosa como el análisis o la explicación.

Sin embargo, no permitas que me malinterpreten.

—La atención indebida, seria y morbosa

excitado por objetos frívolos en su propia naturaleza, no debe confundirse en

personaje

con esa propensión rumiante común a toda la humanidad, y más especialmente

consentido

en por personas de imaginación ardiente.

Ni siquiera era, como podría ser al principio

supuesto, un

condición extrema o exageración de tal propensión, sino principal y

esencialmente

distinto y diferente.

En un caso, el soñador, o entusiasta,

estar interesado

por un objeto generalmente no frívolo, imperceptiblemente pierde de vista este objeto en

desierto de deducciones y sugerencias que emanan de él, hasta que,

al final de

un sueño diurno a menudo repleto de lujo, encuentra el incitamentum o primera causa

de su

reflexiones completamente desvanecidas y olvidadas.

En mi caso, el objeto principal era

invariablemente

frívolo, aunque asumiendo, a través de mi visión alterada, una

importancia refractada e irreal.

Se hicieron pocas deducciones, si es que hubo alguna;

y esos pocos

volviendo pertinazmente sobre el objeto original como centro.

Las meditaciones eran

nunca placentero;

y, al término de la ensoñación, la primera causa,

muy lejos de

fuera de la vista, había alcanzado ese interés sobrenaturalmente exagerado que

fue el

característica predominante de la enfermedad.

En una palabra, los poderes de la mente más

particularmente

ejercitados estaban conmigo, como antes he dicho, los atentos, y son,

con el soñador,

el especulativo.

Mis libros, en esta época, si no sirvieran realmente para irritar la

desorden, participó

serán percibidos, en gran parte, en su carácter imaginativo e intrascendente,

del

cualidades características del trastorno en sí.

Recuerdo bien, entre otros,

el tratado

del noble italiano Coelius Secundus Curio «de Amplitudine Beati Regni dei»;

S t.

la gran obra de Austin, la «Ciudad de Dios»;

y Tertuliano «de Carne Christi»,

en el que la

frase paradójica «Mortuus est Dei filius;

creíble est quia ineptum est:

et sepulto

resucitar;

certum est quia impossibile est» ocupaba mi tiempo indiviso,

para muchos

semanas de laboriosa e infructuosa investigación.

Así parecerá que, sacudido de su equilibrio sólo por cosas triviales,

mi razon aburre

semejanza con ese peñasco oceánico del que habla Ptolomeo Hefestión, que

resistiendo los ataques de la violencia humana, y la furia más feroz de las aguas y

la

vientos, temblaba solo al toque de la flor llamada Asphodel.

Y aunque, para un pensador descuidado, podría parecer un asunto fuera de toda duda,

que el

alteración producida por su desgraciada enfermedad, en la condición moral de Berenice,

haría

proporcionarme muchos objetos para el ejercicio de esa intensa y anormal meditación

cuyo

naturaleza que he tenido algunos problemas para explicar, sin embargo, tal no era de ninguna manera

grado el

caso.

En los intervalos lúcidos de mi enfermedad, su calamidad, de hecho,

me dio dolor, y,

tomando muy en serio el total naufragio de su hermosa y gentil vida,

no caí en reflexionar

frecuente y amargamente sobre los medios maravillosos por los cuales tan extraño

la revolución había tenido lugar tan repentinamente.

Pero estas reflexiones participaron

no de

la idiosincrasia de mi enfermedad, y si tal como hubiera ocurrido,

bajo similar

circunstancias, a la masa ordinaria de la humanidad.

Fiel a su propio carácter,

mi trastorno

se deleitó con los cambios menos importantes pero más sorprendentes forjados en el

marco físico

de Berenice, en la singular y más espantosa distorsión de su vida personal.

identidad.

Durante los días más brillantes de su belleza incomparable, seguramente nunca había

amado

su.

En la extraña anomalía de mi existencia, los sentimientos conmigo, nunca habían sido

del

corazón, y mis pasiones siempre fueron de la mente.

A través del gris de los primeros

mañana —entre las sombras enrejadas del bosque al mediodía— y en el

silencio

de mi biblioteca por la noche, ella había pasado rápidamente por mis ojos, y la había visto, no como

los vivos

y respirando a Berenice, sino como la Berenice de un sueño, no como un ser del

tierra,

terrenal, sino como la abstracción de tal ser, no como una cosa para admirar,

pero para analizar—

no como objeto de amor, sino como tema de la más abstrusa aunque

inconexo

especulación.

Y ahora, ahora me estremecí en su presencia, y palidecí ante ella.

Acercarse;

sin embargo, lamentando amargamente su condición caída y desolada,

recordé que

ella me había amado por mucho tiempo, y, en un mal momento, le hablé de matrimonio.

Y por fin se acercaba el período de nuestras nupcias, cuando, en un

tarde en

el invierno del año, uno de esos días inusualmente cálidos, tranquilos y brumosos

cual

son la nodriza de la hermosa Halcyon1, —Me senté (y me senté, como pensé, solo,

) en el

apartamento interior de la biblioteca.

Pero alzando mis ojos vi que Berenice estaba

antes de

yo.

-

¿Fue mi propia imaginación excitada, o la brumosa influencia de la atmósfera, o

la

crepúsculo incierto de la cámara, o las cortinas grises que caían a su alrededor

figura

—¿Que le provocó un trazo tan vacilante e indistinto?

No podria decir.

ella no hablo

palabra, yo, por nada del mundo podría haber pronunciado una sílaba.

Un escalofrío helado corrió

A través de mi

cuadro;

me oprimía una sensación de angustia insoportable;

una curiosidad que consume

impregnado

mi alma;

y hundiéndome en la silla, me quedé un rato sin aliento

y

inmóvil, con los ojos clavados en su persona.

¡Pobre de mí!

su demacración era

excesivo,

y ni un solo vestigio del ser anterior, acechaba en una sola línea del

contorno.

Mi

miradas ardientes finalmente cayeron sobre el rostro.

La frente era alta, muy pálida y singularmente plácida;

y el otrora embarcadero

el cabello se cayó

parcialmente sobre él, y ensombreció las sienes huecas con innumerables

rizos ahora

de un amarillo vivo, y discordantes discordantemente, en su carácter fantástico,

con el

melancolía reinante en el semblante.

Los ojos estaban sin vida y sin brillo,

y

aparentemente sin pupilas, y me encogí involuntariamente de su mirada vidriosa a la

contemplación de los labios delgados y contraídos.

Ellos se fueron;

y en una sonrisa de

peculiar

significado, los dientes de la cambiada Berenice se revelaron lentamente a mi

vista.

¡Ojalá nunca los hubiera visto, o que, habiéndolo hecho, hubiera muerto!

1 Porque como Júpiter da dos veces siete días de calor en el invierno,

los hombres tienen

llamó a este tiempo clemente y templado la nodriza de la hermosa Halcyon

—Simónides.

Me inquietó el cerrarse de una puerta y, al mirar hacia arriba, descubrí que mi prima había

partió de la cámara.

Pero de la cámara desordenada de mi cerebro, no había,

¡Pobre de mí!

partió, y no sería ahuyentado, el espectro blanco y espantoso de

la

dientes.

Ni una mota en su superficie, ni una sombra en su esmalte, ni una

escritura en

sus bordes, pero lo que ese período de su sonrisa había sido suficiente para grabar en mi

memoria.

Los vi ahora incluso más inequívocamente de lo que los vi entonces.

¡El diente!

-¡el diente!

—estaban aquí, allá y en todas partes, y visible y palpablemente

antes de mí;

largas, estrechas y excesivamente blancas, con los pálidos labios retorciéndose

a cerca de ellos,

como en el momento mismo de su primer desarrollo terrible.

Luego vino el completo

furia de mi

monomanía, y luché en vano contra su extraña e irresistible

influencia.

En el

objetos multiplicados del mundo exterior no tenía más pensamientos que los dientes.

Por estos yo

anhelaba con un deseo frenético.

Todos los demás asuntos y todos los intereses diferentes.

convertirse

absortos en su sola contemplación.

Ellos, ellos solos estaban presentes en el

mental

ojo, y ellos, en su sola individualidad, se convirtieron en la esencia de mi mental

vida.

Yo sostuve

ellos en todas las luces.

Los convertí en cada actitud.

Encuesté a sus

características.

yo

se detuvo en sus peculiaridades.

Reflexioné sobre su conformación.

Reflexioné sobre el

alteración en su naturaleza.

Me estremecí cuando les asigné en la imaginación un

sensible

y poder sensible, e incluso cuando no es asistido por los labios, una capacidad de moral

expresión.

De Mad'selle Salle bien se ha dicho, «que tous ses pas etaient

des

sentimientos», y de Berenice yo creía más seriamente que toutes ses dents

etaient des

ideas

Des ideas!

—¡ah, aquí estaba el pensamiento idiota que me destruyó!

Des ideas!

—ah

¡Por eso los codicié con tanta locura!

Sentí que su posesión

podría solo

devuélveme siempre a la paz, devolviéndome la razón.

Y la tarde se cerró sobre mí así, y luego vino la oscuridad, y se demoró,

y

se fue, y el día amaneció de nuevo, y las nieblas de una segunda noche se disiparon ahora.

reuniéndome, y todavía me senté inmóvil en esa habitación solitaria;

y todavía me senté enterrado

en la meditación, y todavía el fantasma de los dientes mantuvo su terrible

ascendencia

como, con la más vívida y espantosa distinción, flotaba en medio de la

cambio de luces

y sombras de la cámara.

Por fin irrumpió en mis sueños un grito como de

horror y consternación;

y luego, después de una pausa, sucedió el sonido de turbado

voces, entremezcladas con muchos gemidos bajos de pena o de dolor.

me levanté de mi

asiento y, abriendo de par en par una de las puertas de la biblioteca, vio de pie en el

antecámara una sirvienta, toda llorando, que me dijo que Berenice era... no

más.

La habían atacado con epilepsia temprano en la mañana, y ahora,

en el cierre de

la noche, la tumba estaba lista para su inquilino, y todos los preparativos para el

entierro

fueron completados.

Me encontré sentado en la biblioteca, y nuevamente sentado allí

solo.

Eso

Parecía que acababa de despertar de un sueño confuso y excitante.

Yo sabía que

Ahora era medianoche, y yo era muy consciente de que desde la puesta del sol

Berenice tuvo

sido enterrado.

Pero de ese período lúgubre que intervino no tenía nada positivo, por lo menos.

el menos

sin comprensión definida.

Sin embargo, su memoria estaba repleta de horror, horror más

horrible por ser vago, y el terror más terrible por la ambigüedad.

Fue un temible

página en el registro de mi existencia, escrita por todas partes con oscuro, y horrible, y

recuerdos ininteligibles.

Me esforcé por descifrarlos, pero en vano;

mientras siempre y

pronto, como el espritu de un sonido difunto, el chillido estridente y penetrante de un

voz femenina

parecía estar resonando en mis oídos.

Había hecho una obra, ¿cuál era?

me pregunte a mi mismo el

pregunta en voz alta, y los ecos susurrantes de la cámara me respondieron, «¿qué fue

¿eso?"

En la mesa a mi lado ardía una lámpara y cerca de ella había una pequeña caja.

era de no

carácter notable, y lo había visto con frecuencia antes, porque era el

propiedad de la

médico de cabecera;

pero ¿cómo llegó allí, sobre mi mesa, y por qué me estremecí en

con respecto a eso?

Estas cosas no podían ser explicadas de ninguna manera, y mis ojos en

la longitud se redujo a las páginas abiertas de un libro y a una oración subrayada

en esto.

los

palabras fueron las singulares pero sencillas del poeta Ebn Zaiat, «Dicebant mihi sodales

si sepulchrum amicae visitarem, curas meas aliquantulum fore levatas.

«¿Por qué entonces, como yo

los examiné, los cabellos de mi cabeza se erizaron y la sangre

de mi

cuerpo se congele dentro de mis venas?

Hubo un ligero toque en la biblioteca

puerta,

y pálido como el inquilino de una tumba, un sirviente entró de puntillas.

Su aspecto era

salvaje

con terror, y me hablaba con voz trémula, ronca y muy baja.

Qué dijo

¿él?

—algunas frases entrecortadas que escuché.

Habló de un grito salvaje que inquietó al

silencio de la

noche —de la reunión de la familia— de una búsqueda en dirección

del

sonido;

—y luego sus tonos se volvieron emocionantemente claros mientras me susurraba una

violado

tumba —de un cuerpo desfigurado y amortajado, aún respirando, aún palpitando,

¡Aún vivo!

Señaló las prendas; estaban embarradas y cubiertas de sangre.

no hablé,

y el

me tomó suavemente de la mano;

— estaba marcado con la huella de uñas humanas.

Él

dirigí mi atención a algún objeto contra la pared;

—Lo miré por algunos

minutos;

—era una pala.

Con un chillido salté a la mesa y agarré la caja que

poner

sobre ello.

Pero no pude abrirla a la fuerza;

y en mi temblor se deslizó de mi

manos y

cayó pesadamente y se hizo añicos;

y de ella, con un sonido de traqueteo,

allí se desplegó

algunos instrumentos de cirugía dental, entremezclados con treinta y dos pequeños,

blanco y

Sustancias de aspecto marfil que estaban esparcidas de un lado a otro por el suelo.

Más de 2 millones de letras

Canciones en diferentes idiomas

Traducciones

Traducciones de alta calidad a todos los idiomas

Búsqueda rápida

Encuentra los textos que necesitas en segundos